Early Impacts of 4% Floor Include Price Dip and More Competition

The new 4% floor for noncompetitive tax credits has spurred competition among low-income housing developments. Keep reading for a breakdown of how the credits work and what the new floor could mean for developers.

Low-Income Housing Tax Credits

Low-income housing tax credits (LIHTC)—dollar-for-dollar federal income tax credits—are a product of the Tax Reform Act of 1986. They are one of the primary incentives for the development of affordable housing in the U.S. The federal government allots these credits to state housing agencies, which run their state’s LIHTC program. Each state agency awards the credits to developers who apply and qualify for them. To qualify, developments must meet specific requirements, such as reserving a minimum number of units at restricted rents for tenants below a certain income threshold.

Rather than use the tax credits for themselves, many developers seek syndicators, who fund a large part of the development costs by paying a discounted price for the credits. Syndicators then aggregate the tax credits from multiple deals into larger funds and offer the funds to outside investors who have large federal tax liability. The result of LIHTC programs is threefold:

- Affordable rental housing for low income individuals and families

- Less lender-financed liabilities for developers

- Federal income tax credits for investors

Types of Tax Credits

There are two types of tax credits, known as “4% tax credits” and “9% tax credits.” The primary difference between 4% tax credits and 9% tax credits is the process for obtaining them. This process has led to tax credits also being called “noncompetitive” and “competitive” tax credits, respectively.

That is, states’ authority to award 4% tax credits is not strictly limited. Instead, they are generally awarded to applicants as long as at least 50% of the development is funded by federal subsidies or tax-exempt bonds.

On the other hand, 9% tax credits have no such subsidy or bond financing requirements. Applications for these credits are highly competitive because, in addition to unit and income constraints, their availability is subject to the states’ allocation authority, which is strictly limited.

Calculating the Credit Rate Percentage

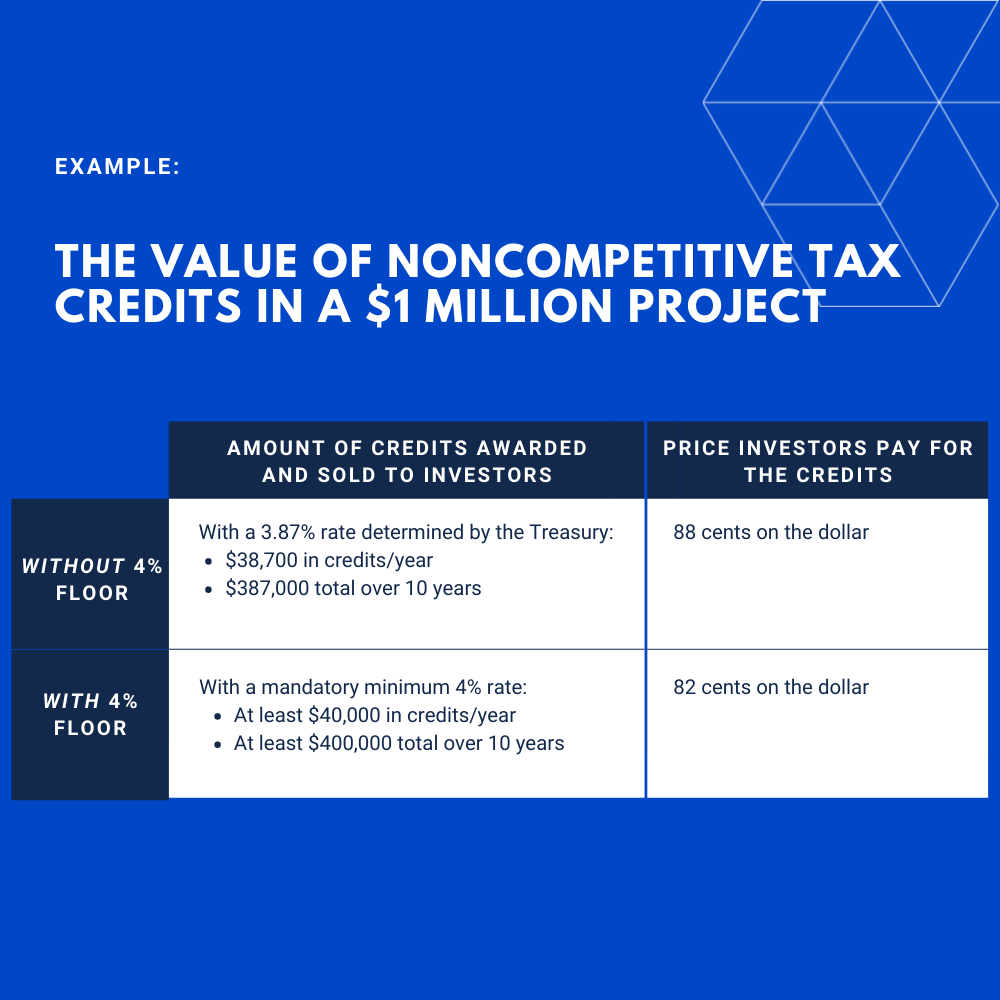

The Tax Reform Act of 1986 required housing agencies to use a 4% or 9% rate during the inaugural year of the program. But since 1988, the formula set forth in Section 42(b)(1)(B) of the tax code has been used to calculate the actual rate that determines the tax credits’ awarded value. Section 42 states that the percentage “shall be the percentages which will yield over a 10-year period [tax credits] which have a present value equal to” either 70% (for competitive projects) or 30% (for noncompetitive projects) “of the qualified basis” of the building. The “qualified basis” includes construction and renovation costs, excluding non-depreciable costs such as the price of the land. Thus, the rate that achieves the statutory, target present value of the total subsidy determines the yearly percentage of tax credits granted during the 10-year period following the award.

The Treasury Secretary may, and many times has, determined that a rate less than 4% or 9% will result in a total, present value subsidy of 70% or 30%, respectively. In such cases, the names “4% tax credits” and “9% tax credits” become nothing more than informal designations for the awards. In fact, the rate for noncompetitive tax credits has not reached 4% since 1987, and the last time the formula calculated a 9% rate for competitive tax credits was 1990.

The Tax Credit Floor

In 2015, the Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act set the rate for determining the value of competitive credits to a 9% floor. This means that even if the Treasury’s formula results in a lower rate, the 9% rate must be used. A recipient of competitive tax credits is now certain to receive credits with an annual value of at least 9% of the qualified basis of the building. This floor has also raised the present value of the total subsidies above the statutory minimum of 70%.

A similar floor for noncompetitive tax credits was not set until the Certainty and Disaster Tax Relief Act of 2020, which set the floor at 4%.

The Tax Credit Floors’ Impact

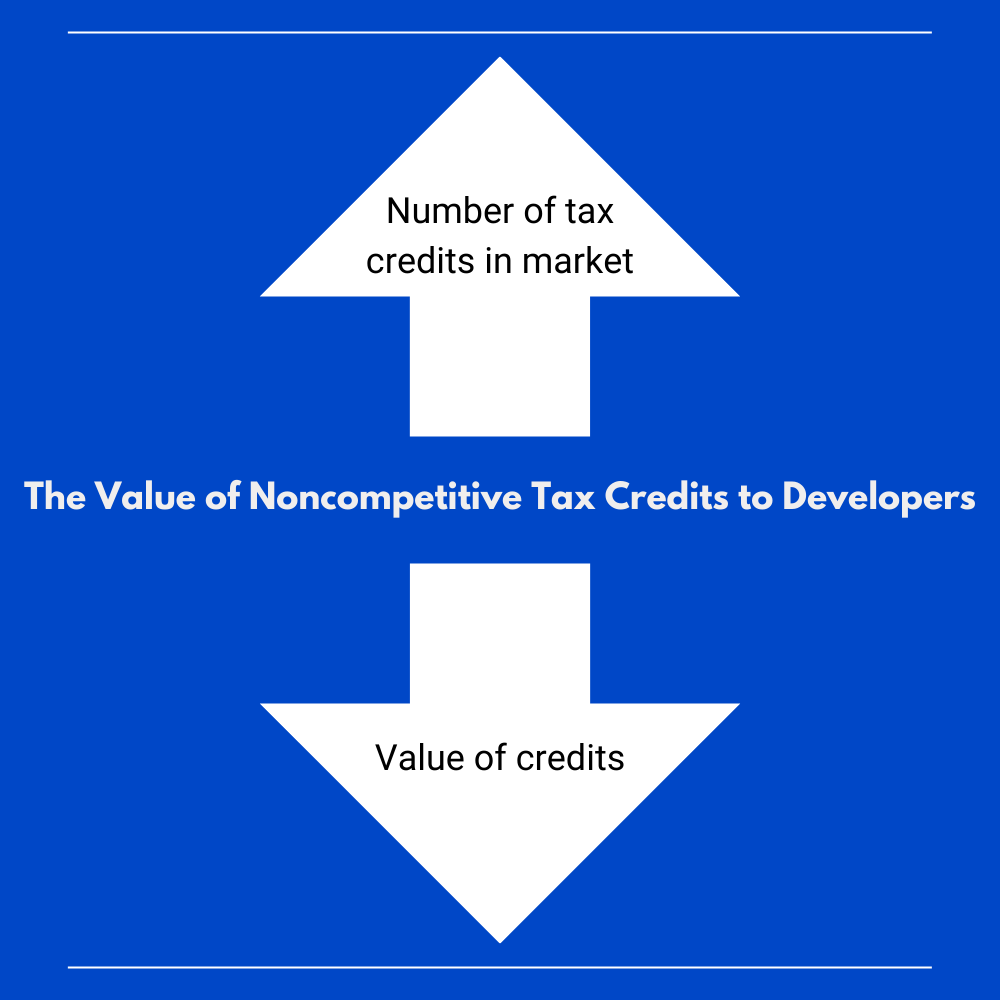

Since the number of tax credits produced by a given deal is dependent on the tax credit rate (4% or 9%), raising the prior floating rate to a 4% floor flooded the market with tax credits overnight.

A market saturation of noncompetitive tax credits has lowered their value, sometimes by as much as 5 to 6 cents on the dollar. This change in value, along with a substantial increase in the number of developers applying for credits, has lead to developers receiving less funding from investors in exchange for the tax credits. Additionally, it has allowed syndicators to be more selective when deciding which projects to fund, causing unexpected delays in development timelines.

Issues Facing the Industry

The influx of noncompetitive tax credits joins other issues currently facing the industry, including rent abatement, eviction moratoriums, price hikes and delays on building materials and permits.

Without a limit on 4% tax credit awards, developers could continue to realize decreased value for their tax credits. As the first year of the 4% floor plays out, including new applications and upcoming awards, industry participants should watch how their counterparts respond to the increased demand. This will help them adjust accordingly to best position themselves for the future.

Please contact Baxter Geddie or any member of Phelps’ Business team if you have questions or need compliance advice and guidance.